Students at Bucknell and in the College of Engineering are exposed to a bevy of extracurricular learning opportunities, both on campus and off. Recently, Prof. Donna Ebenstein, biomedical engineering department chair, sent five engineers spanning four disciplines and a pair of class years to the University of Delaware for the Design for the Developing World Workshop, which is run by Bucknell chemical engineering graduate Julie Karand ’12, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Delaware.

The two-day workshop invited early career science and engineering students to learn how to design medical devices for developing country contexts, using scenarios from sub-Saharan Africa. Students worked hands-on in teams with coaching provided by international mentors. The Bucknell cohort was joined by students from Delaware, Lehigh University and the University of Pittsburgh.

“Every workshop has its own objective,” says Jean Marie Ngabonziza ’26, computer engineering, one of the six Bucknell engineers to make the nearly three-hour journey. “Attending workshops is a very good chance to learn something new. It is moving from the structure of class to engaging in real-world opportunities.”

Ziheng Zeng ’23, chemical engineering, also attended the workshop, which interested her because of its focus on Africa and its health care system.

“I liked learning about different areas of the world,” says Zeng, a native of China. “People in the U.S. aren’t always aware of the suffering going on elsewhere or the challenges associated with health care. It is astonishing to find out it can be so bad.”

After an early morning departure from Bucknell, Ngabonziza, Zeng and fellow Bucknell students Nolan Lwin ’26, Simbi Maphosa ‘23 and Eren Ugur ’26 arrived at Delaware.

The engaging workshop commenced with visiting scholars from South Africa and Tanzania introducing life in their countries, including the culture, foods and health care challenges. Students learned there are often thefts from hospitals because of the unmet needs of the public.

That background provided facts the students used the next two days as they developed prototypes. One of the key ideas shared by the workshop facilitators was to keep the end user in mind when designing. Both Ngabonziza and Ziheng found ways to incorporate this good advice throughout the weekend.

Students began the ideating and prototyping phase of the workshop by designing a wallet with a small group of fellow participants.

“I like a physical wallet, but a lot of people don’t want a wallet, just something that can stick to their phone or be in their phone,” says Zeng. “Each table had to come up with one final design, and that was really challenging because everyone wants something different. We designed a wallet that could stick to a phone but that could also detach and you could have the information on your phone. We tried to combine all the ideas, but it would be a challenge for the design to work in the real world.”

The wide range of preferences encountered by Zeng’s group helped her realize how important — and difficult — designing for the end user is. And it was helpful when brainstorming started for the next portion of the workshop.

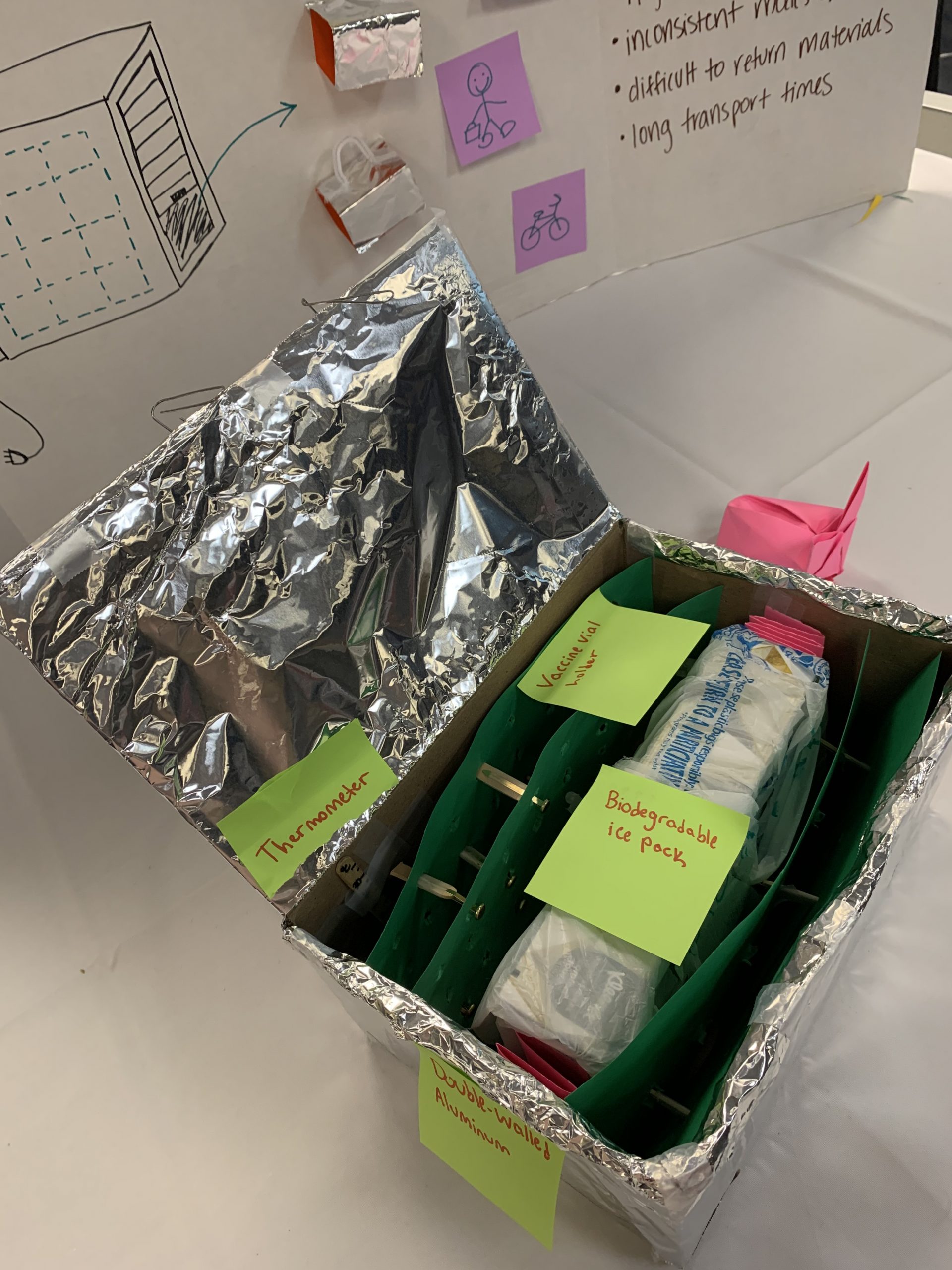

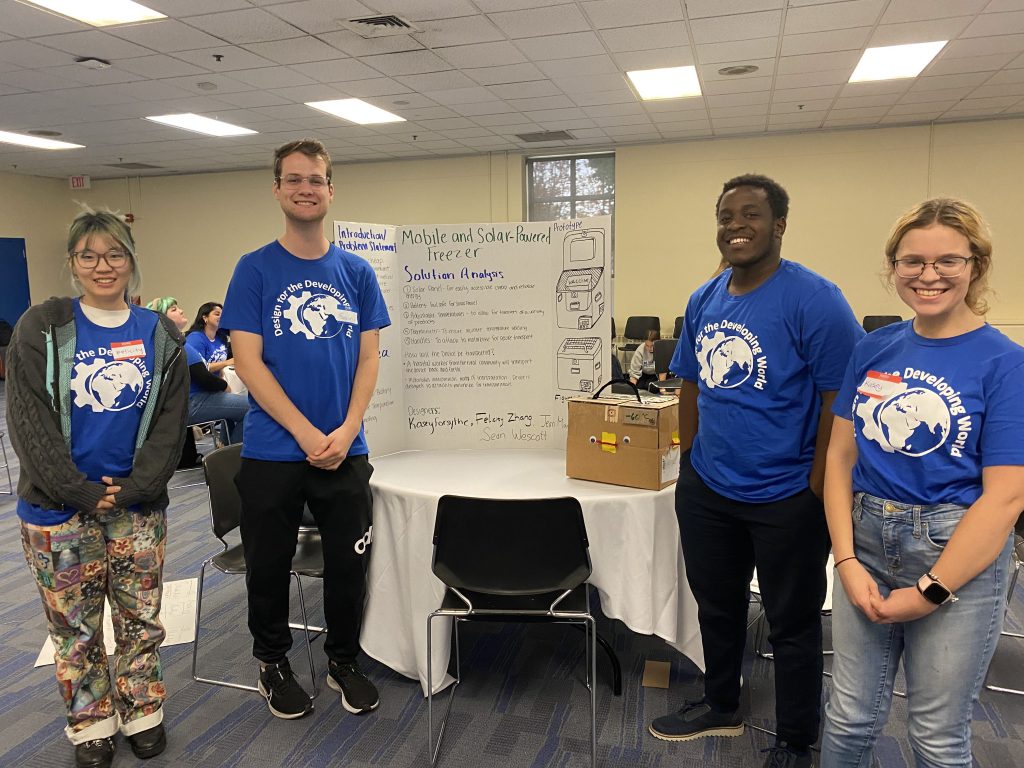

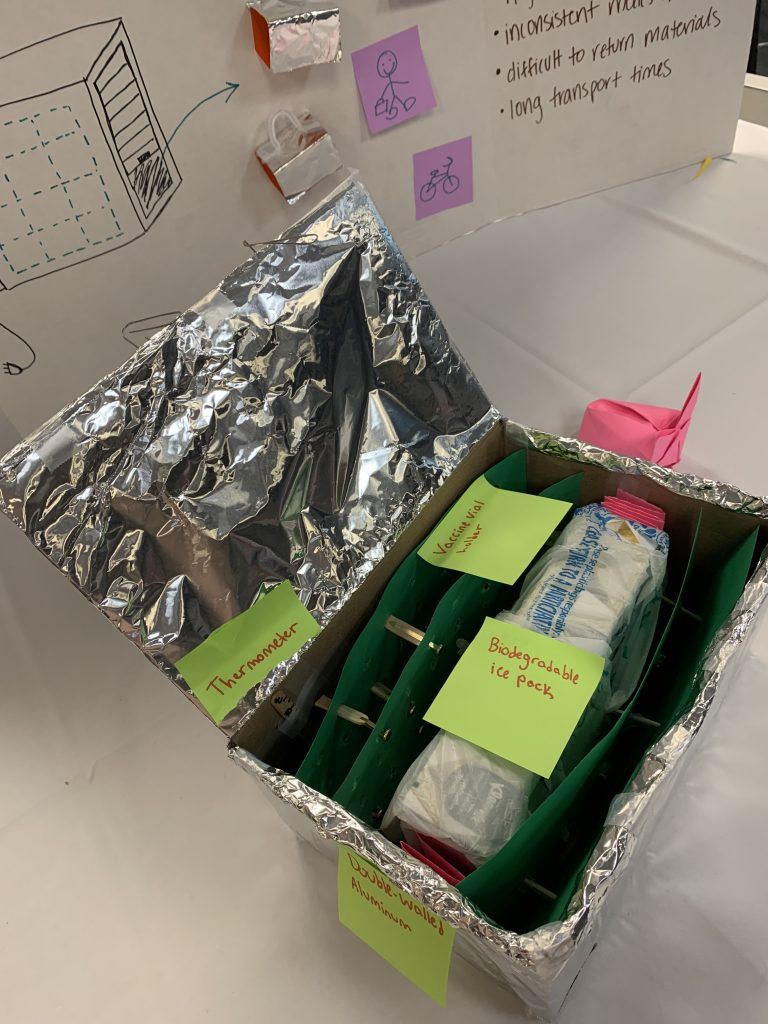

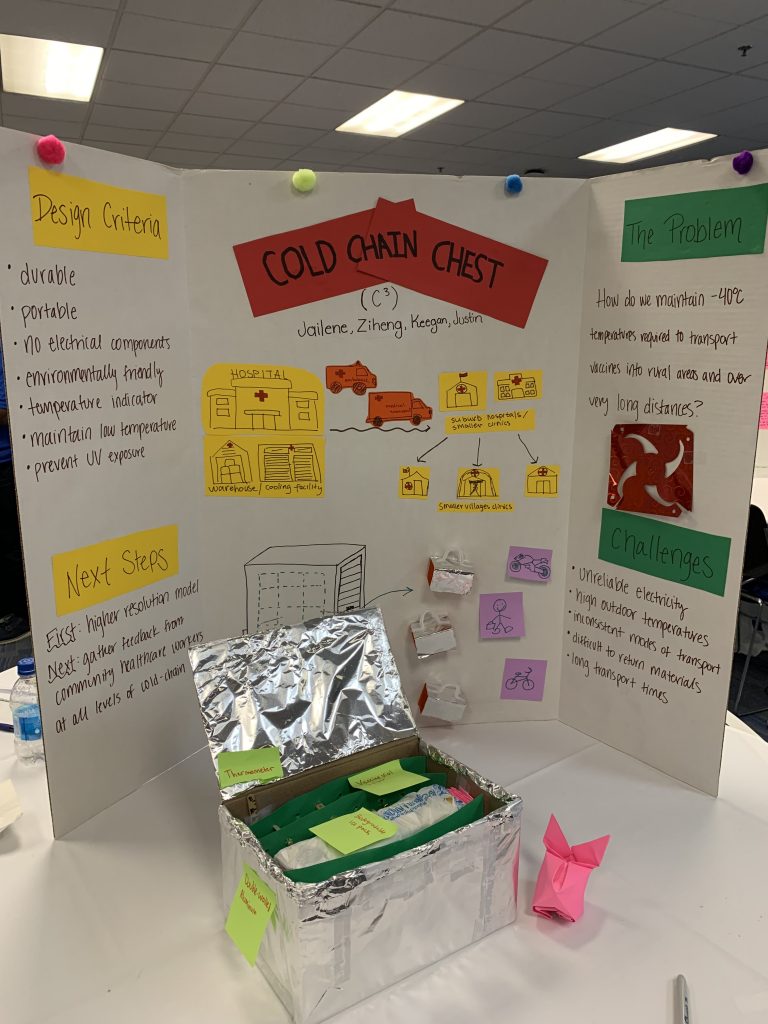

New groups were formed for the next project and both Ngabonziza and Zeng were teamed with students from Lehigh and Pittsburgh. The goal was to develop a prototype to aid the cold chain transportation of vaccines from urban centers of Africa to hard-to-reach rural areas. Brainstorming commenced toward the end of the first day of the workshop, and the groups finished their designs on day two before presenting during a poster expo.

Ngabonziza’s group initially developed a prototype that relied on a chemical reaction to keep the vaccine cold during transport. But when a workshop facilitator posed the question of who would refill the system with the chemical substance, they pivoted to a new design that used a solar panel and battery to power the cooling mechanism.

“Our second design was much simpler,” says Ngabonziza. “We often focus on the technical part of the designs, but we need to zoom out and see how it is used in the real world.”

Zeng’s team focused more on insulation when designing its prototype, allowing an ice pack to provide the cooling power for up to 24 hours. They also added straps to their prototype, recognizing it would provide an easier way to transport for someone riding a bike or walking vs. the delivery trucks we picture in the U.S.

“We were trying to focus on something that is one-time use and low cost to reduce the temptation of theft,” says Zeng. “We included an ice pack compartment and a thermometer so the temperature can be monitored.”

Both Ngabonziza and Zeng thoroughly enjoyed the experience and would recommend fellow Bucknell engineers take advantage of similar opportunities. They were able to learn about different places, connect with students from other schools, strengthen existing relationships with their fellow Bucknellians and participate in hands-on design activities.